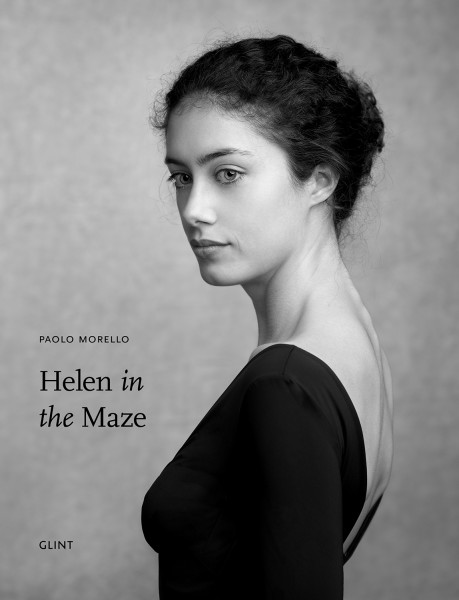

Helen in the Maze

Buy now your copy by mailing to: orders@glintbooks.com

34 x 44 cm, hardback, 64 pages, tritone with varnish, 65 Euro

“For this new chapter of my research, the initial theme was loving one’s own image more than oneself. Where other than Milan, a global fashion capital, does a place exist that is better suited for reflecting on a topic which is actually very old? – that is, the rift between being and appearance, between image…

Read more“For this new chapter of my research, the initial theme was loving one’s own image more than oneself. Where other than Milan, a global fashion capital, does a place exist that is better suited for reflecting on a topic which is actually very old? – that is, the rift between being and appearance, between image and identity, a question first posed by Parmenides in about 500 bce, but still of great topical interest today. Our lives are steeped in images and we are constantly besieged by images. We love our image, and we cultivate it and attend to it. We delegate to it the task of representing us. We have made it a cult object. Ours is a civilisation of images, we are told. Image conditions what we buy, and to a great extent determines our frustrations and our happiness. Compulsively, we send images to friends, and to recipients we do not even know; social networks reveal the most intimate moments of our daily lives, in deference to the principle that nothing exists unless it is not communicated. This obsessive need for self-representation, which is such a distinctive part of our age, is radically redefining the functions of the portrait. The photographic portrait is the symbolic place where the terms image and identity collide. Every portrait is a projection onto photosensitive paper of an inextricable bundle of expectations, urgent needs, ambitions, challenges, and fears, all in an endless game of mirrors, pitting what I think I know of myself against what I would like others to see, what I discover unexpectedly against what I dream of being. A portrait is an instrument of introspection, of growth, of examination. An opportunity to enhance one’s self-awareness Every portrait questions its own subject. What pleasure, or apprehension, curiosity or wonder, what need to share, or show o€, led you to pose? The need to vanquish time, to leave an enduring trace of your likeness? To indelibly set down your real appearance, or what you thought, or would always have liked to be? Every portrait asks a crucial question of its subject, and constantly re-poses it: who am I?”.

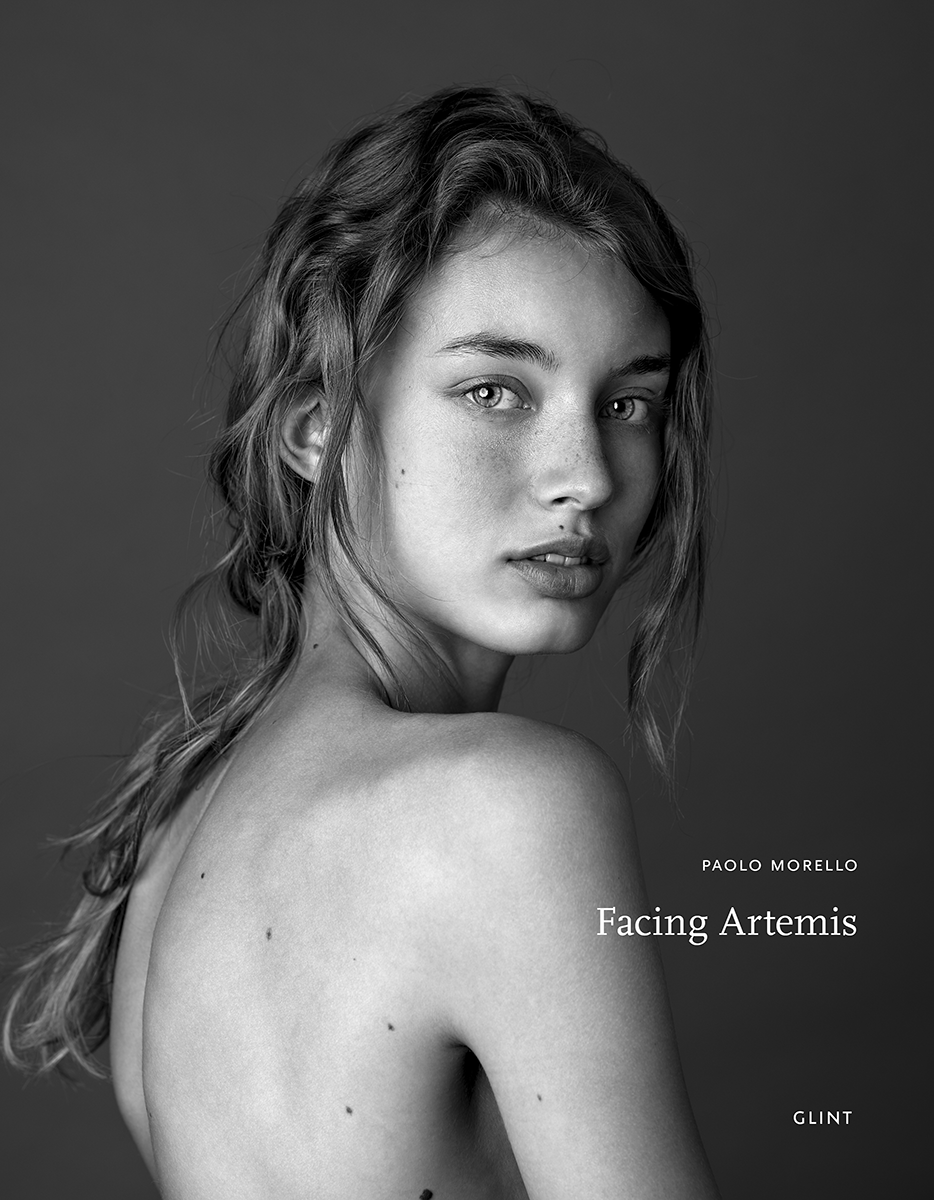

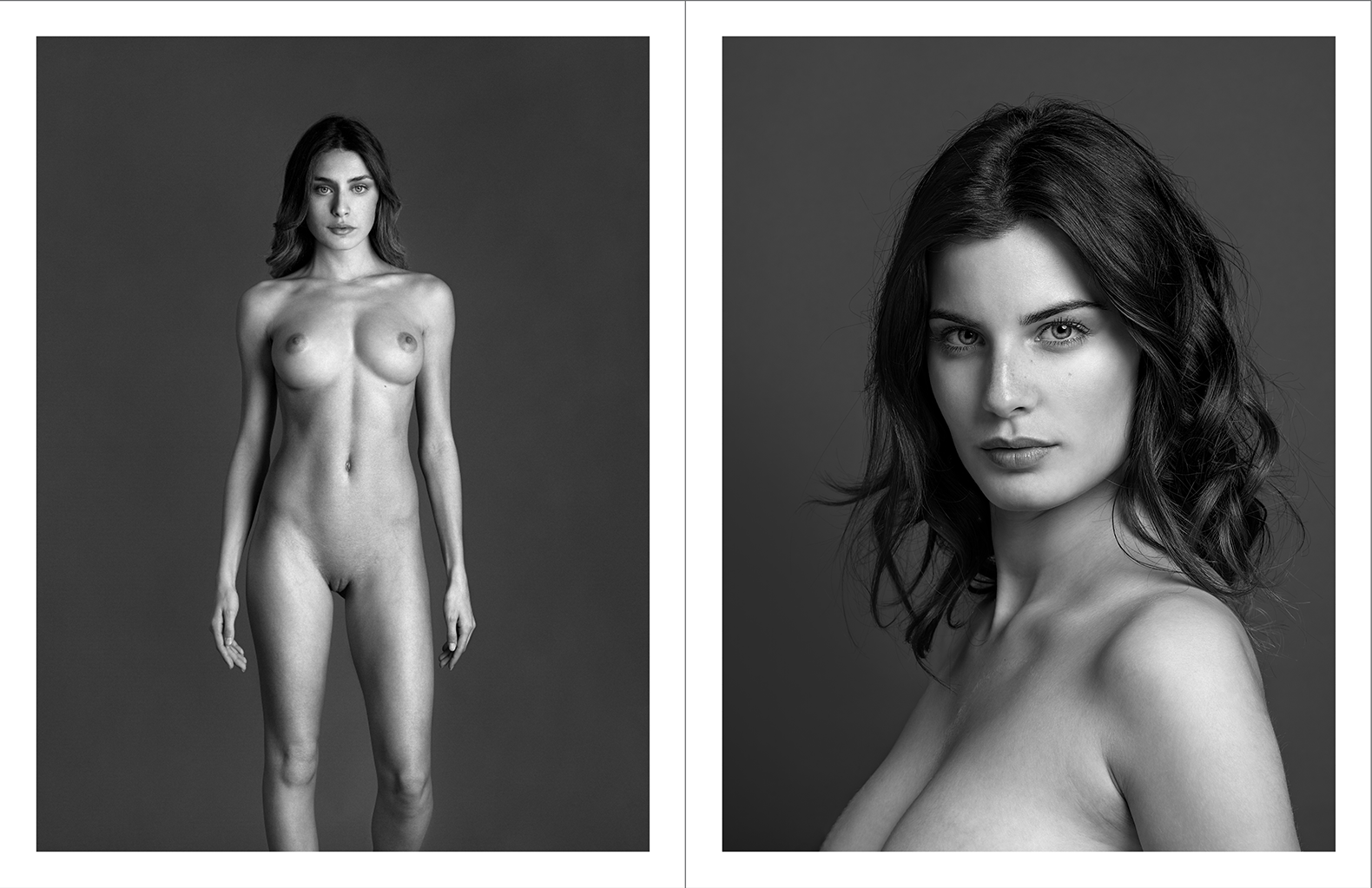

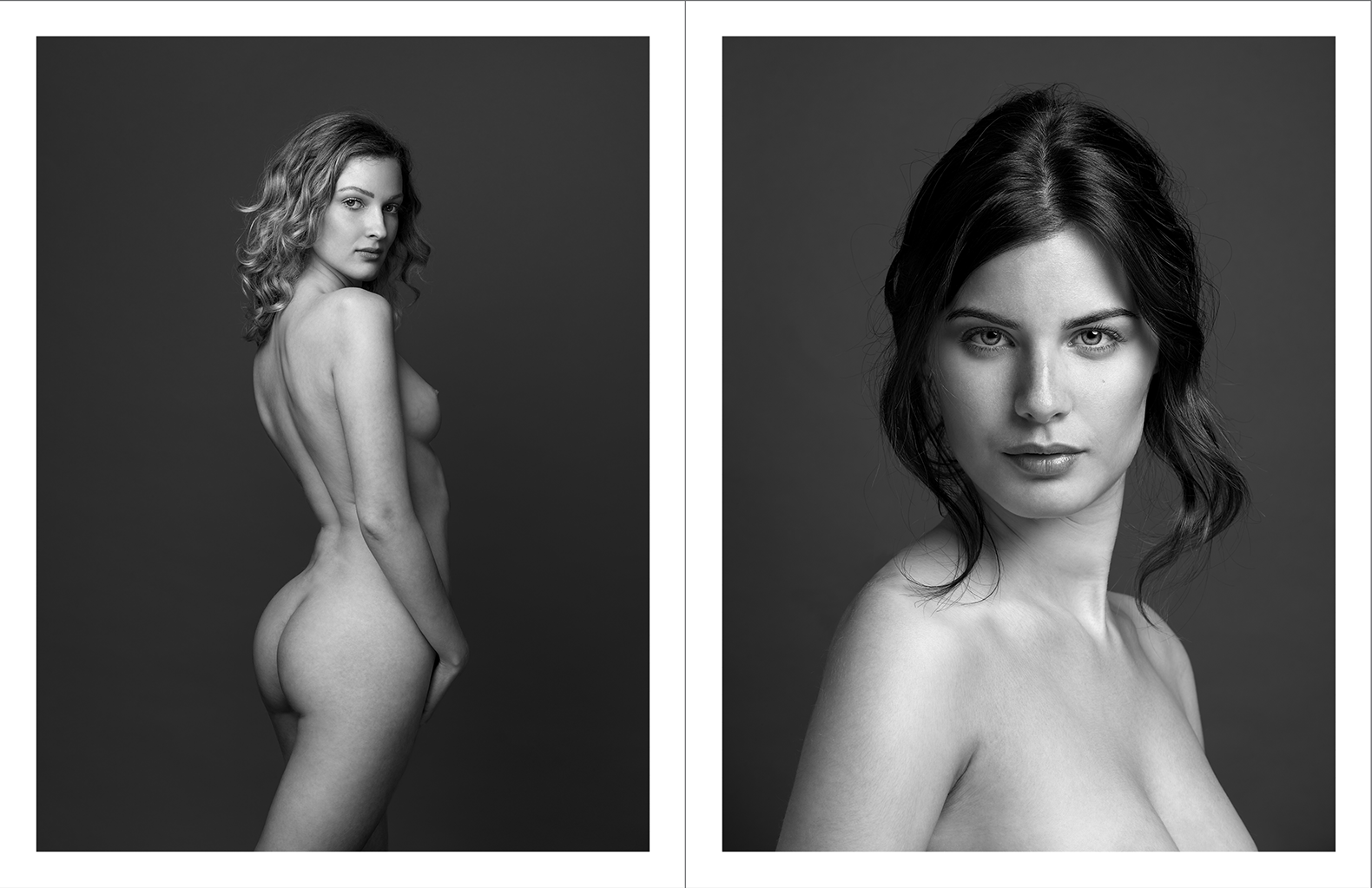

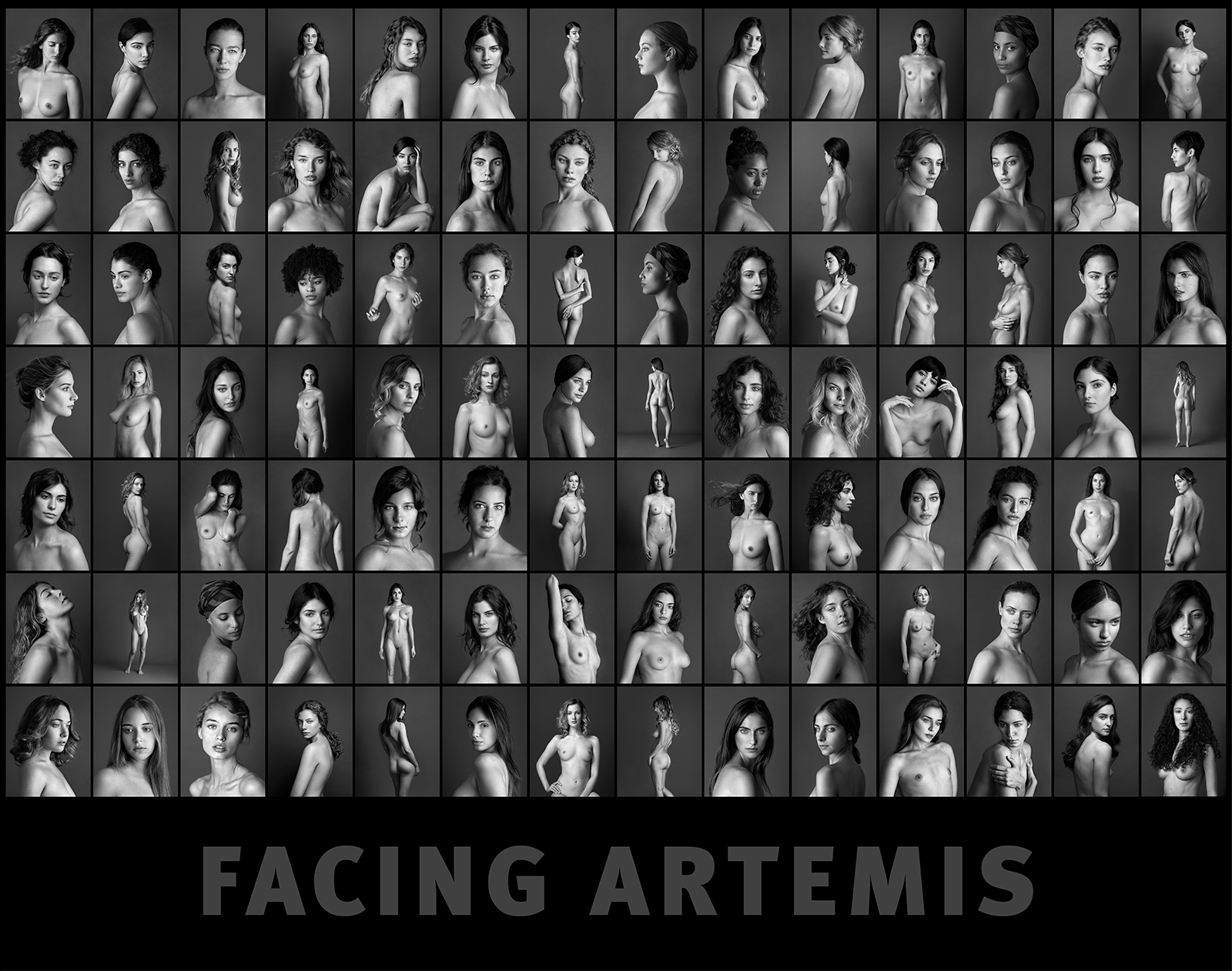

Read lessFacing Artemis

24 x 32 cm, 122 pages, 100 tritone plates with varnish, hardback. English edition. 45 euros.

“Muse, sing of Artemis, sister of the Far-shooter, the virgin who delights in arrows, who was fostered with Apollo”: thus opens the first of the two Homeric Hymns dedicated to the goddess. She excels “supreme among the immortals both in thought and in deed”, continues the second Hymn: Artemis, “whose shafts are of gold, who…

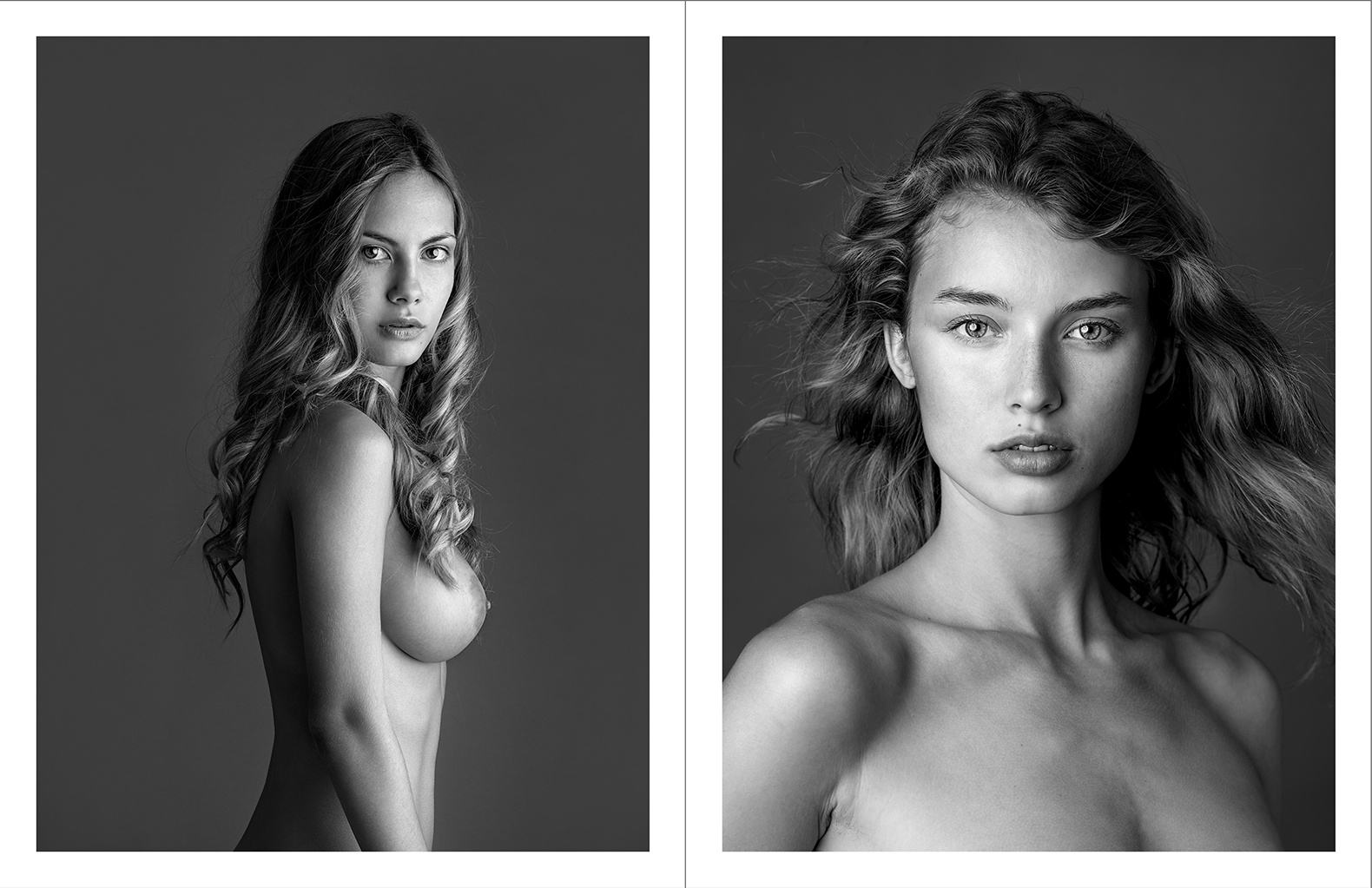

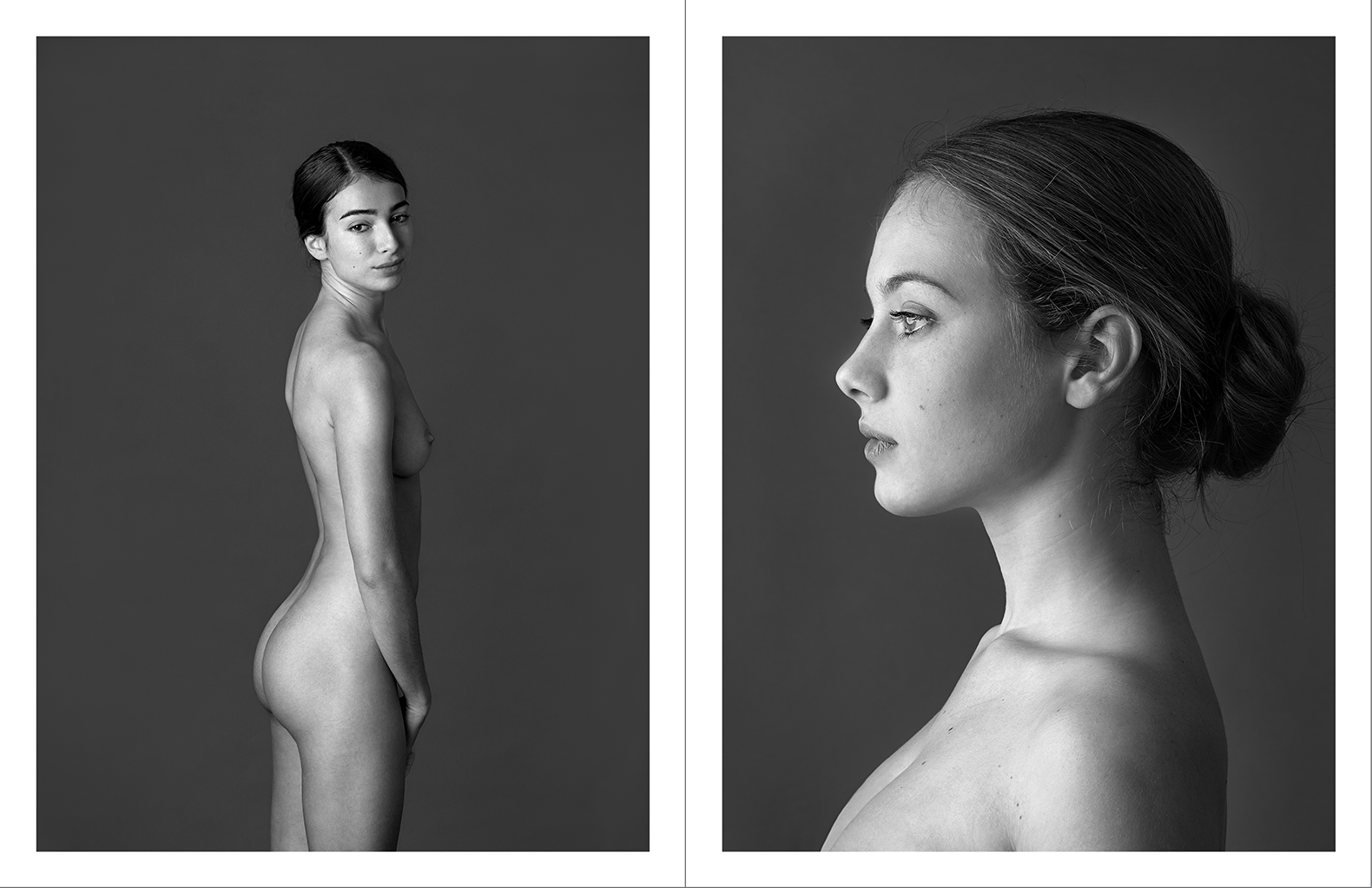

Read more“Muse, sing of Artemis, sister of the Far-shooter, the virgin who delights in arrows, who was fostered with Apollo”: thus opens the first of the two Homeric Hymns dedicated to the goddess. She excels “supreme among the immortals both in thought and in deed”, continues the second Hymn: Artemis, “whose shafts are of gold, who cheers on the hounds, the pure maiden, shooter of stags, who delights in archery, own sister to Apollo with the golden sword. Over the shadowy hills and windy peaks she draws her golden bow, rejoicing in the chase, and sends out grievous shafts. The tops of the high mountains tremble and the tangled wood echoes awesomely with the outcry of beasts: earthquakes and the sea also where fishes shoal. But the goddess with a bold heart turns every way destroying the race of wild beasts”. Four centuries later, during the first half of the third century before Christ, Callimachus imagined her as an adolescent, on the lap of Zeus. She makes a request of him: “Give me to keep my maidenhood, Father, forever: and give me to be of many names, that Phoebus may not vie with me. And give me arrows and a bow […] But give me to be Bringer of Light and give me to gird me in a tunic with embroidered border reaching to the knee, that I may slay wild beasts. And give me sixty daughters of Oceanus for my choir – all nine years old, all maidens yet ungirdled; and give me for handmaidens twenty nymphs of Amnisus who shall tend well my buskins, and, when I shoot no more at lynx or stag, shall tend my swift hounds. And give to me all mountains; and for city, assign me any, even whatsoever thou wilt: for seldom is it that Artemis goes down to the town. On the mountains will I dwell and the cities of men I will visit only when women vexed by the sharp pang of childbirth call me to their aid”.

Of the many stories of Artemis, we shall address only one on this occasion: her deadly, fortuitous encounter with Actaeon. It forms a myth that already enjoyed widespread popularity in ancient times, and we now know it through several literary variants and numerous figurative representations. The best-known textual version is found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. During a hunting expedition, the Latin poet tells us, Actaeon, son of the King of Thebes, “wandering through the unfamiliar woods with unsure footsteps”, reaches a clearing, where there is a grotto of extraordinary beauty, and a spring. He arrives there by chance: “for so fate would have it” (“sic illum fata ferebant”). It so happens that at that very moment Artemis is bathing in that spring. Her handmaidens have helped her to undress, and are now pouring water over her body from capacious ewers. The naked nymphs and goddess become aware of the man’s presence and, blushing with shame, begin to utter screams. Artemis, writes Ovid, “stood turning aside a little and cast back her gaze; and though she would fain have had her arrows ready, what she had she took up, the water, and flung it into the young man’s face. And as she poured the avenging drops upon his hair, she spoke these words foreboding his coming doom: ‘Now you are free to tell that you have seen me all unrobed – if you can tell’.” Actaeon is transformed into a stag by the furious goddess: his arms become legs, antlers begin to emerge on his head, and his body is covered with a dappled fur. Actaeon falls prey to terror. He flees, and is amazed at his own speed. He wants to scream, but can only bell, like a deer. Sensing him as prey, his pack of hounds begins to follow him, and they soon block his path and tear him to pieces. Torn apart by his own dogs: that is the horrendous end of Actaeon, guilty – according to Ovid – of having seen Artemis naked, by chance.

The bodies of the gods are sacred; seeing the nude body of a goddess is sacrilege. Again Callimachus, recalling the laws of Kronos: “Whosoever shall behold any of the immortals, when the god himself chooses not, at a heavy price shall he behold”. Seeing, punished as a crime: that is the crucial theme that forms the inspiration for this book.

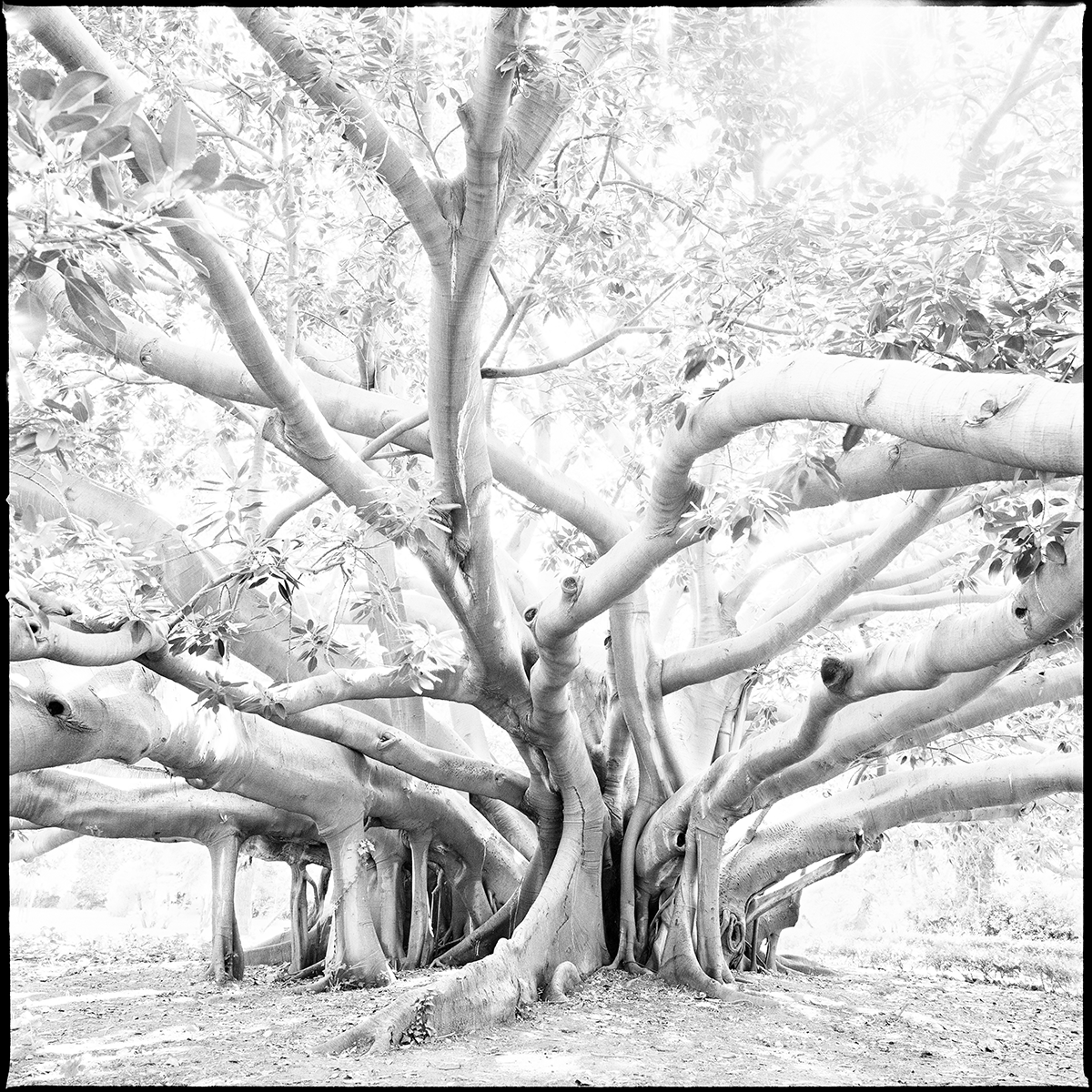

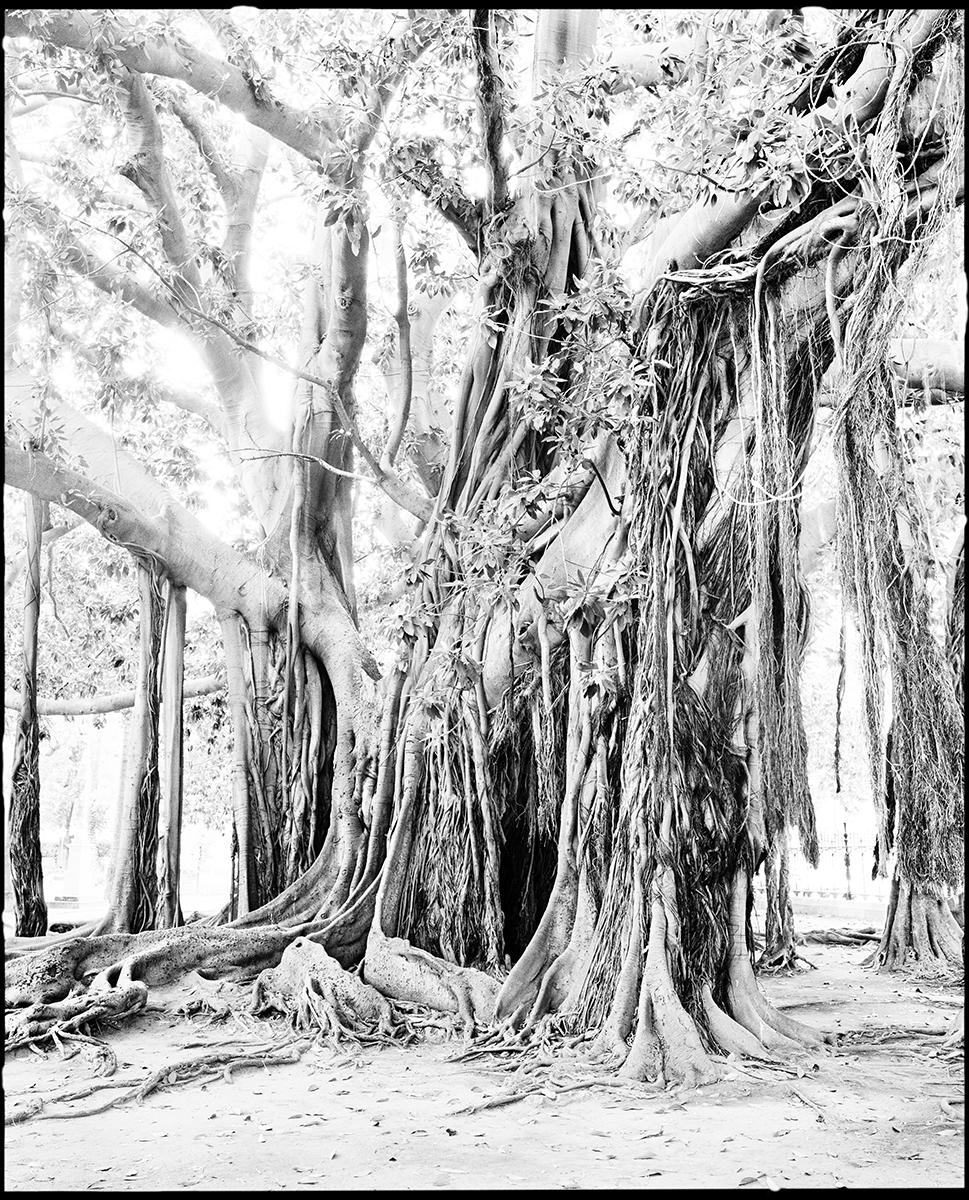

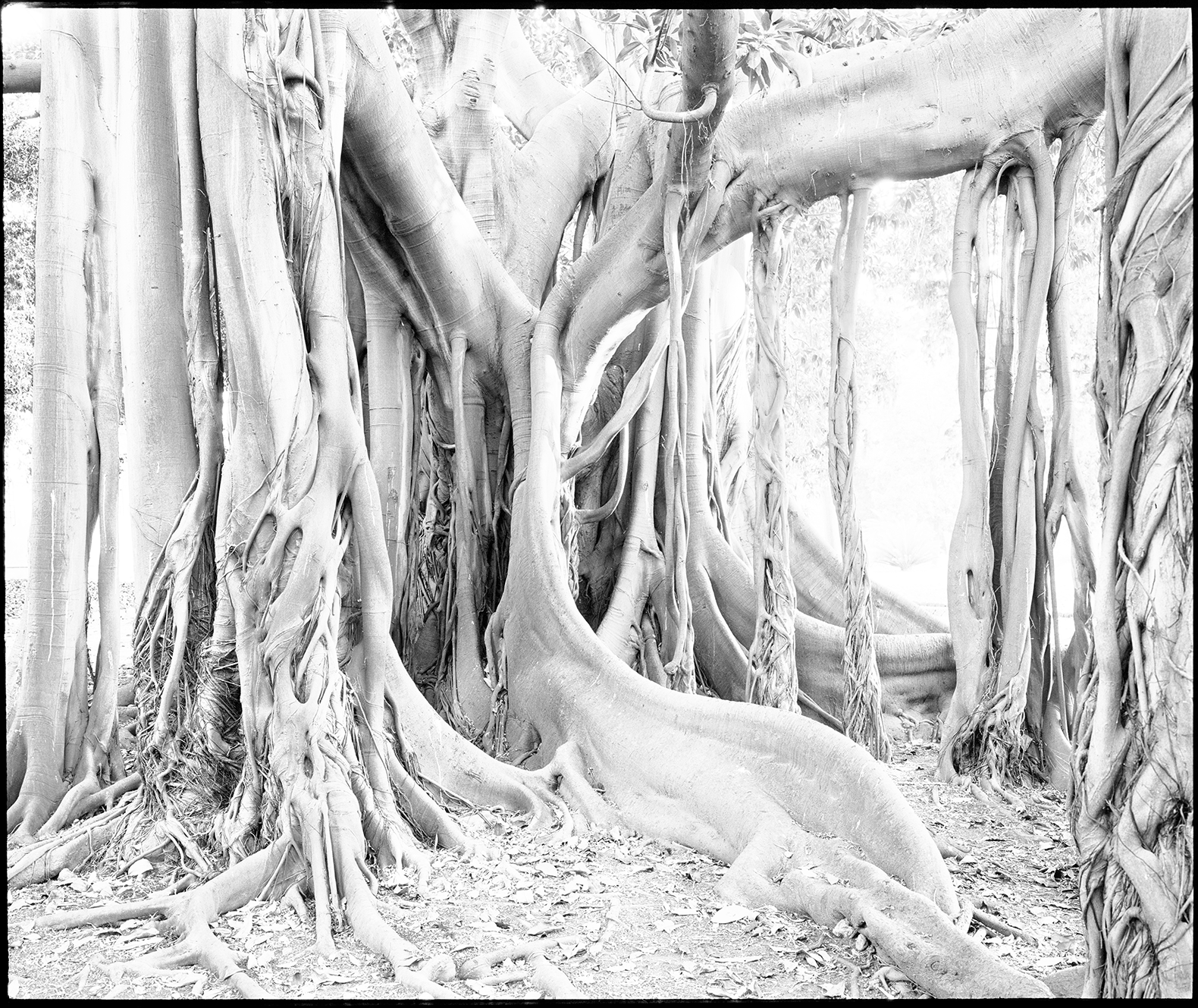

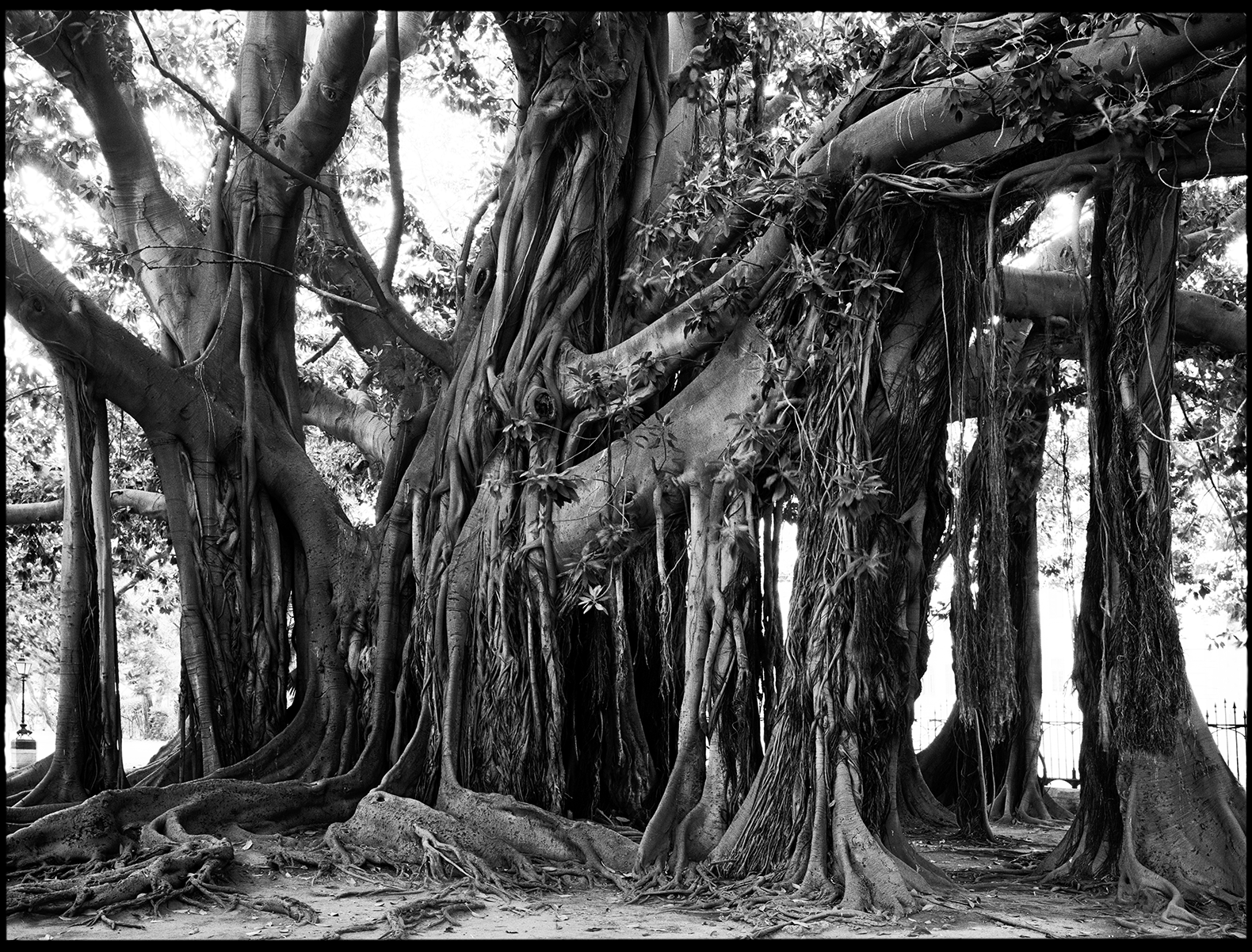

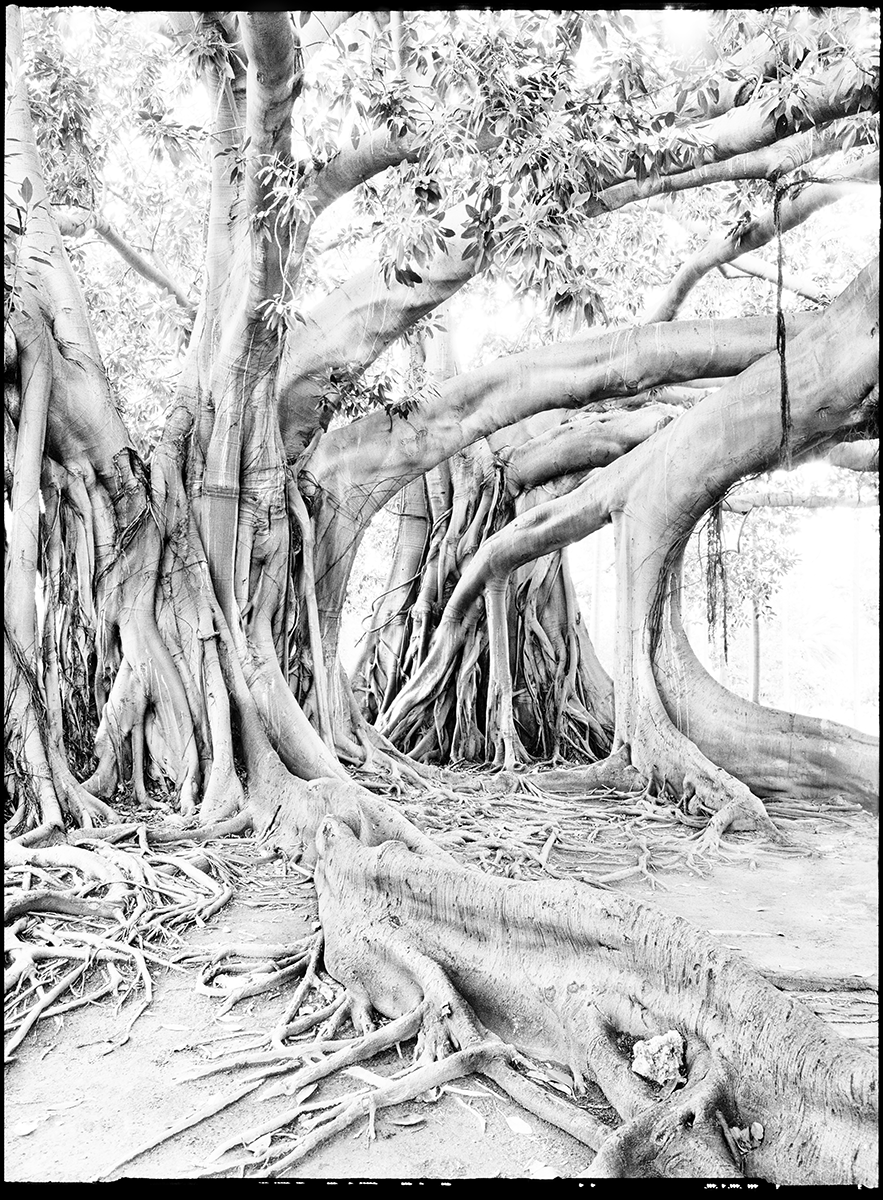

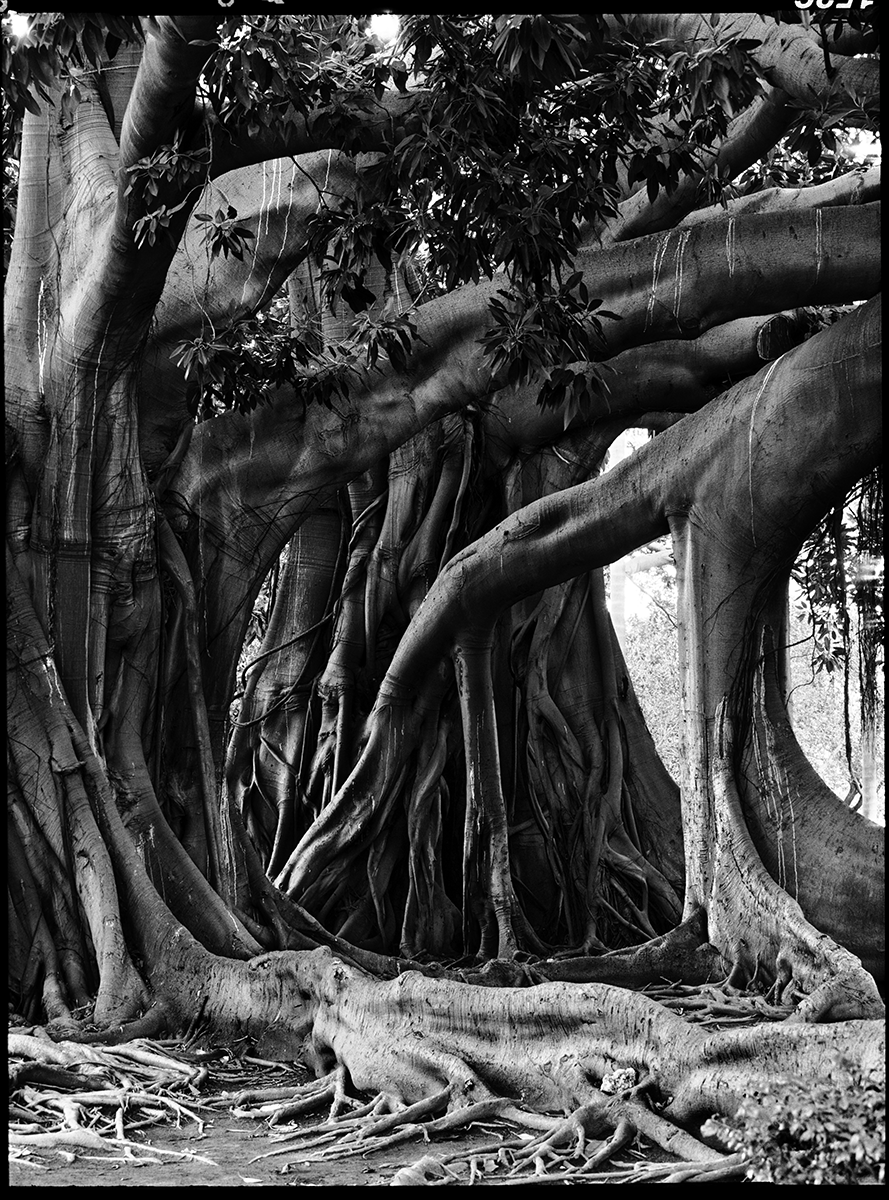

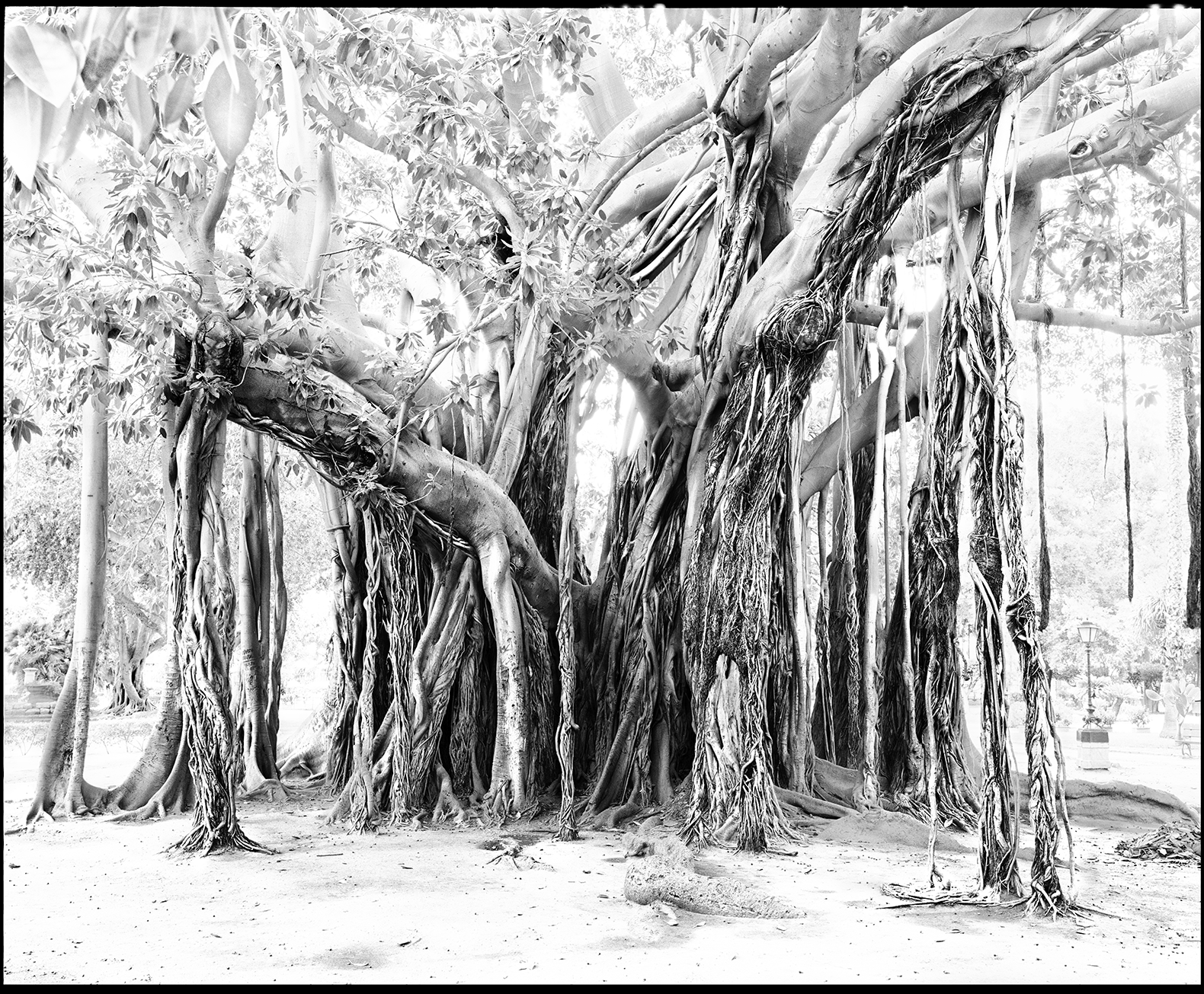

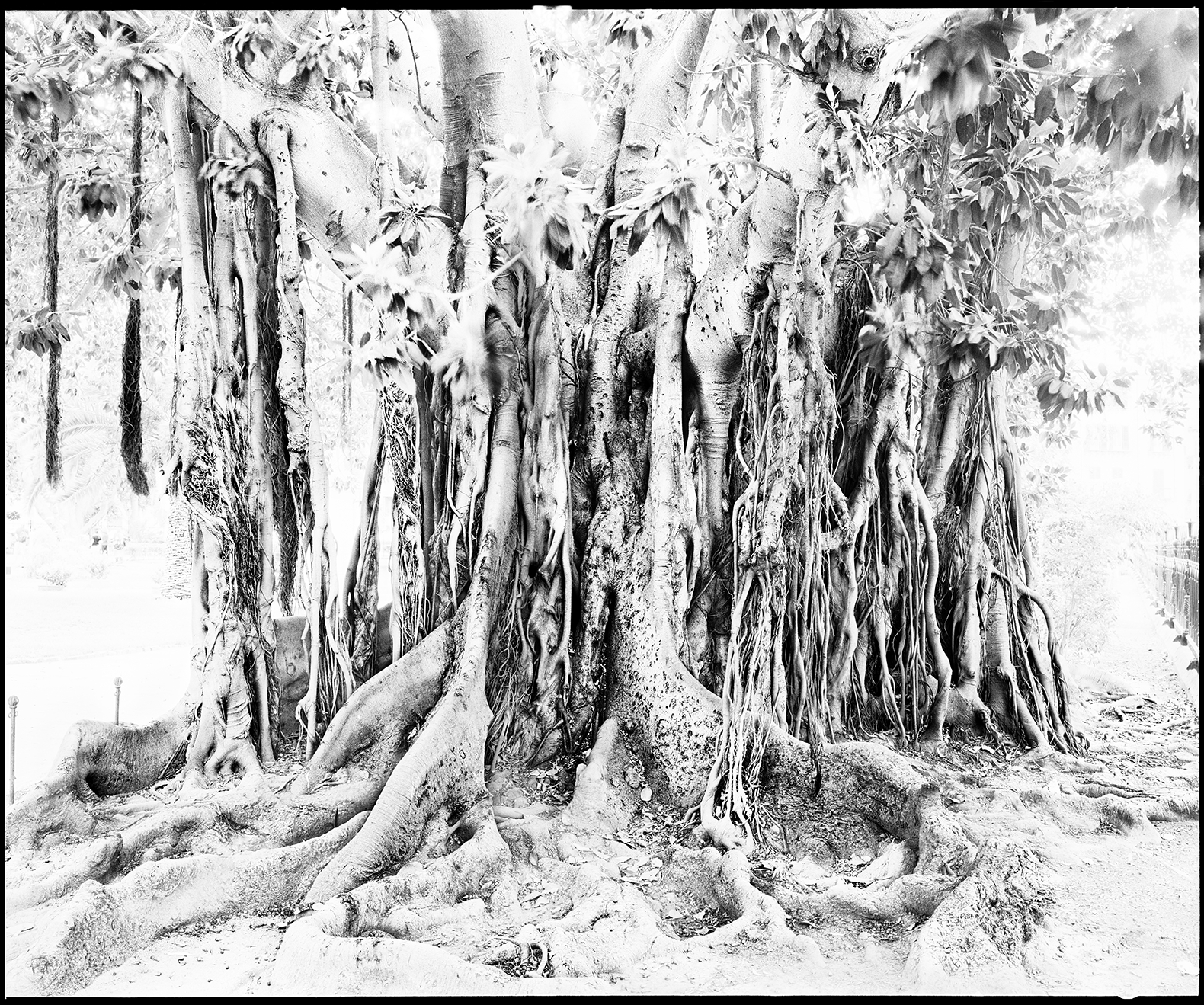

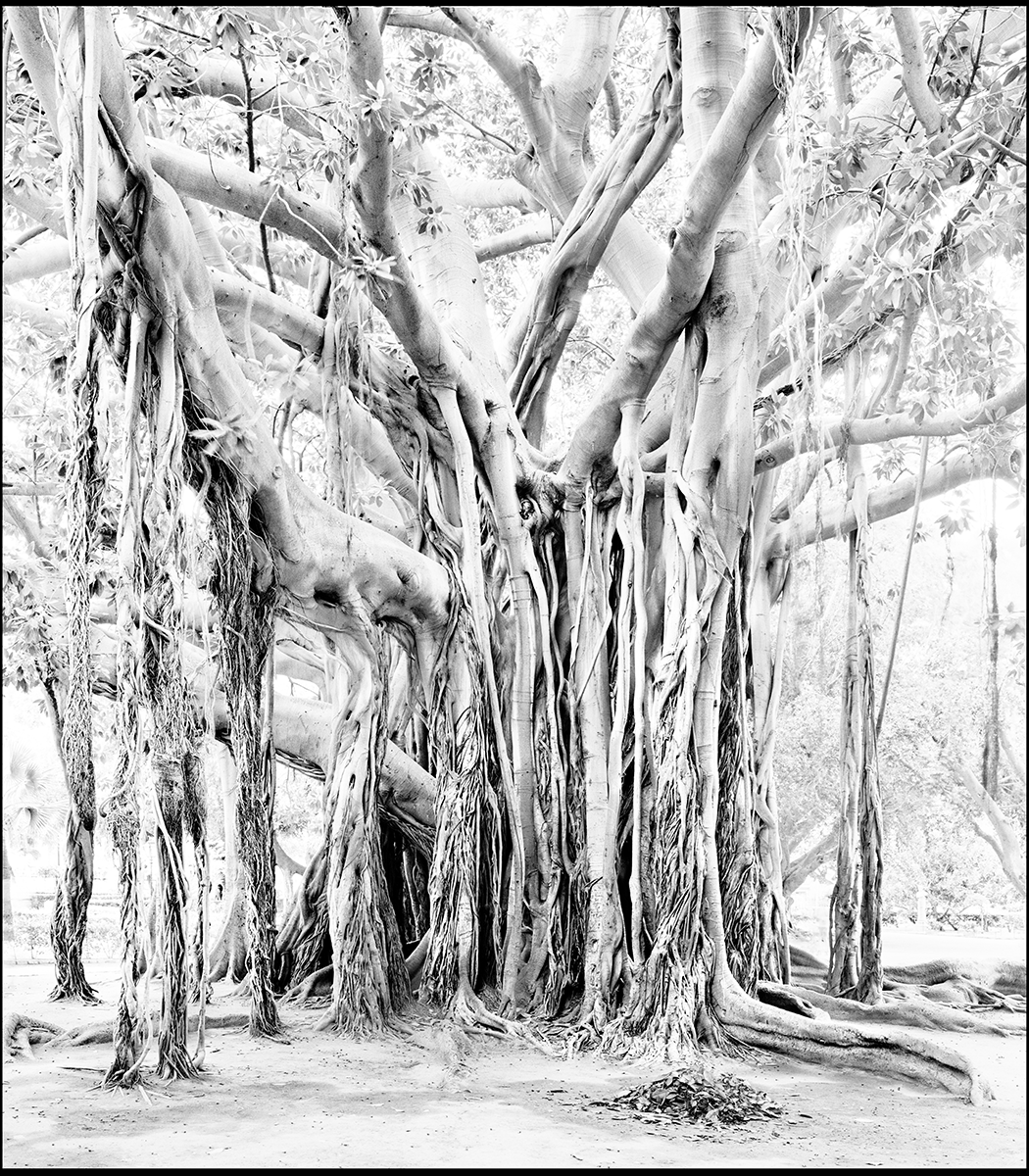

Read lessFicus

34 x 44,5 cm, 40 pages, 22 tritone plates with varnish, hardback, Italian edition. Isbn 978-87928-12-9. 65 euros.

In India, a huge tree, with large, heart-shaped leaves, grew near the temple of Mahabodhi. It was an old specimen of Ficus religiosa; in Sanskrit, its name — Ashwattha — means ‘that which changes’. According to legends, under that tree Siddharta Gautama sat a long time in meditation, until he got the Bodhi, that is the awakening. For this reason,…

Read moreIn India, a huge tree, with large, heart-shaped leaves, grew near the temple of Mahabodhi. It was an old specimen of Ficus religiosa; in Sanskrit, its name — Ashwattha — means ‘that which changes’. According to legends, under that tree Siddharta Gautama sat a long time in meditation, until he got the Bodhi, that is the awakening. For this reason, that banyan tree is known as the Sri Maha Bodhi, or the Bodhi Tree. Still today, in that place there is a great banyan tree, which is said to descend from that under which the Buddha was enlightened. It is considered a sacred tree, and therefore the name of Ficus religiosa was given to its species. Believers of many religions go on pilgrimage there. Gentle and mighty, generous in affording a shelter to wayfarers caught short by rainstorms or exhausted by the summer heat, its name recurs often in old sacred Indian books and in Buddhist legends. In the Chandogya Upanisad, Svetaketu learns from his father how such a gigantic tree can come from a tiny seed, and how in that Nothing the essence of every thing is hidden. Another species — the Ficus benghalensis — in Sanskrit is called Nyagrodha, which means ‘that which grows downwards’. What makes these trees so monumental and moving is the framework of aerial roots, which, reaching the ground, become ancillary trunks, and help to support the weight of the foliage. If one agrees that these trees could have a symbolical value, and that their marvellous shapes could be a teaching to men, then one will understand how the issue that the banyan tree raises is that of rooting. It is not just a matter of the strength of the roots, but rather of the will to connect the top with the bottom. The strength of the result depends on this will. Leaves and roots depend on each other: without the latter, the former would die, and vice versa. It is essential that there is an effective connection so that this mutual function can take place. Without a good link, sap could not rise to the top, and, conversely, the energy synthesized by the leaves could not come back to the ground. For these reasons, banyan trees recur in many religions’ symbology, with the name of Tree of the World, with the celestial specularly superimposed to the mundane. It reminds wayfarers that the Top and the Bottom belong to each other.

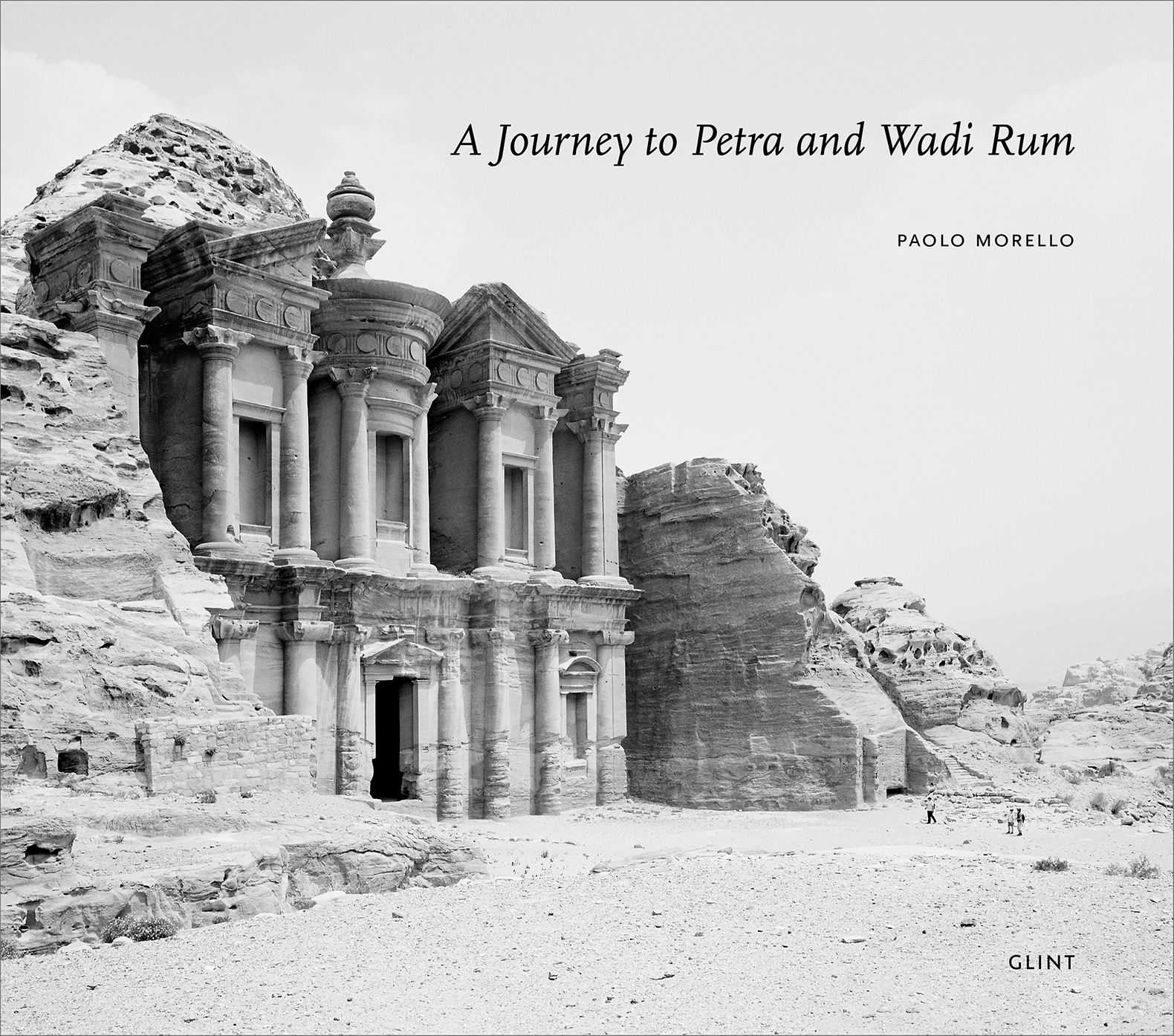

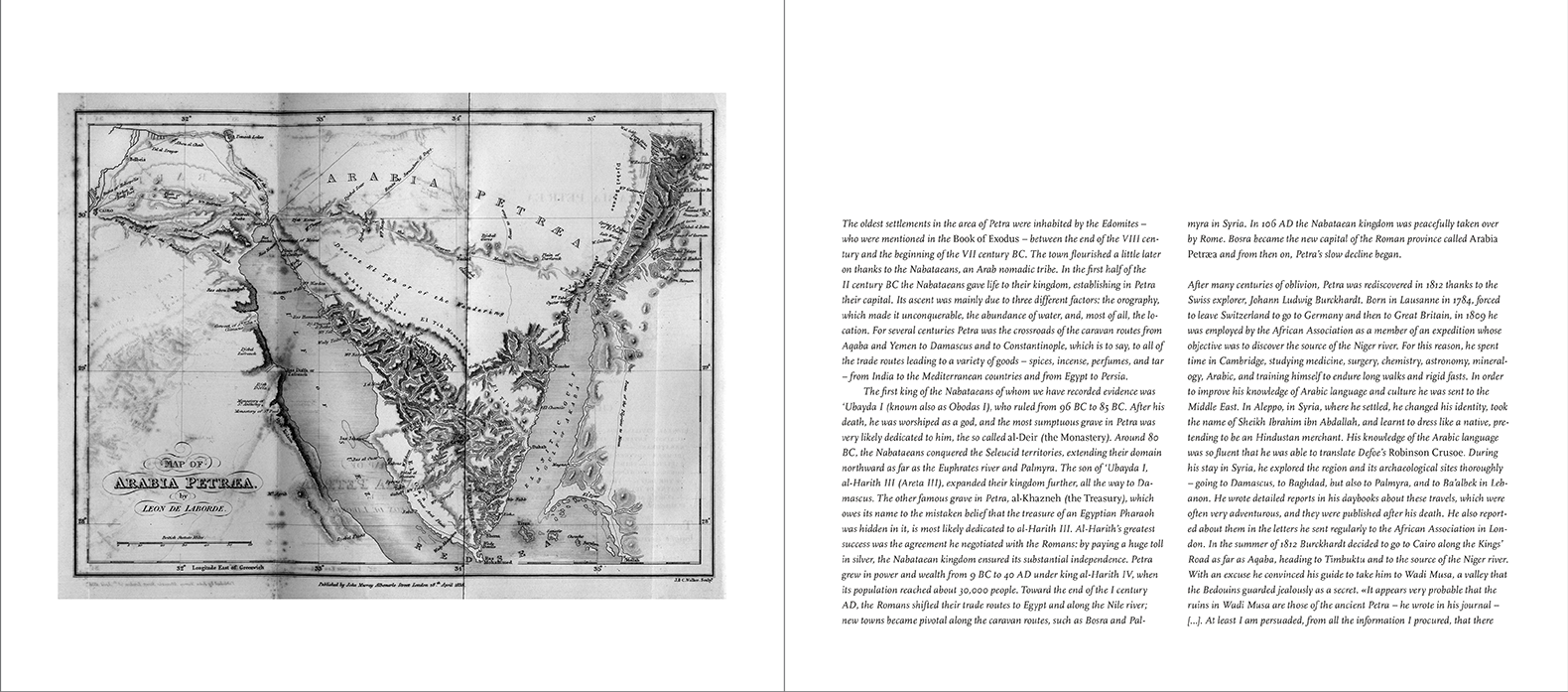

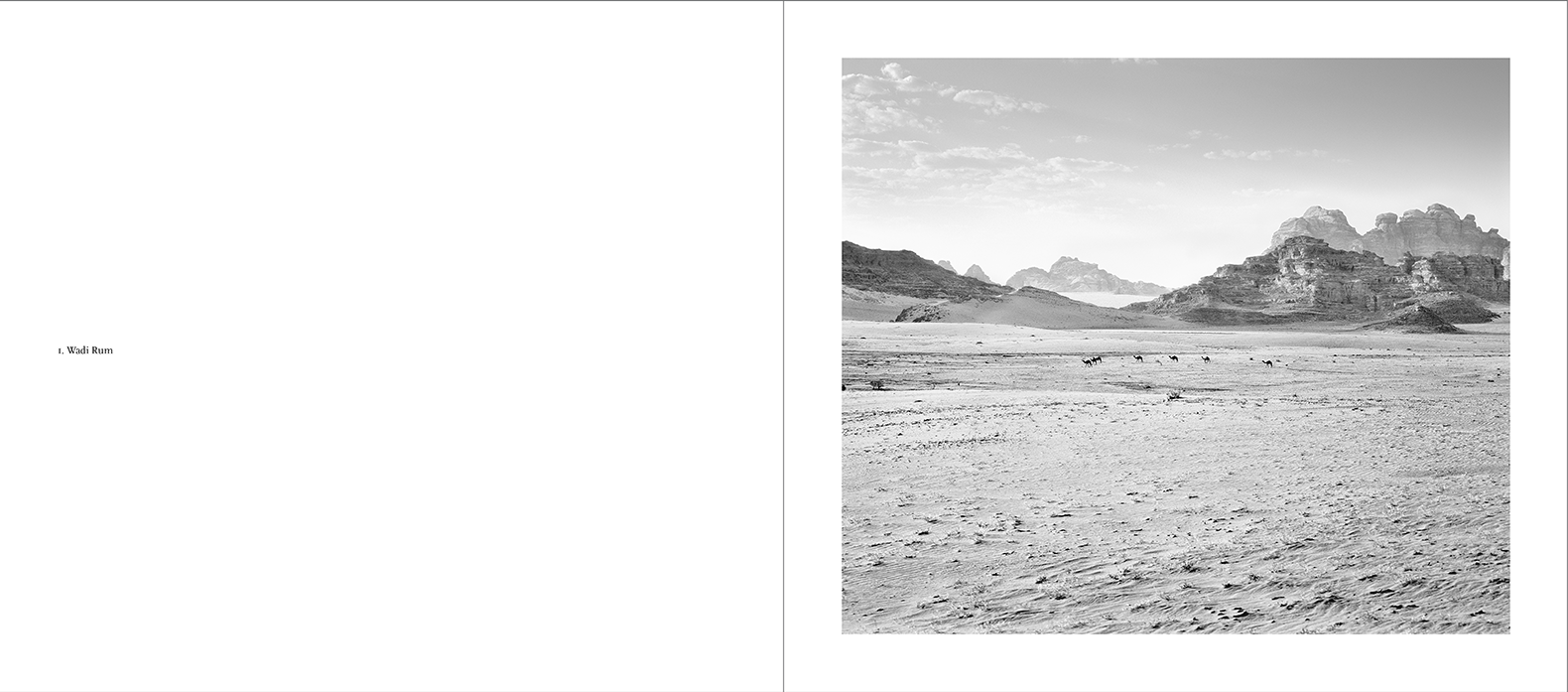

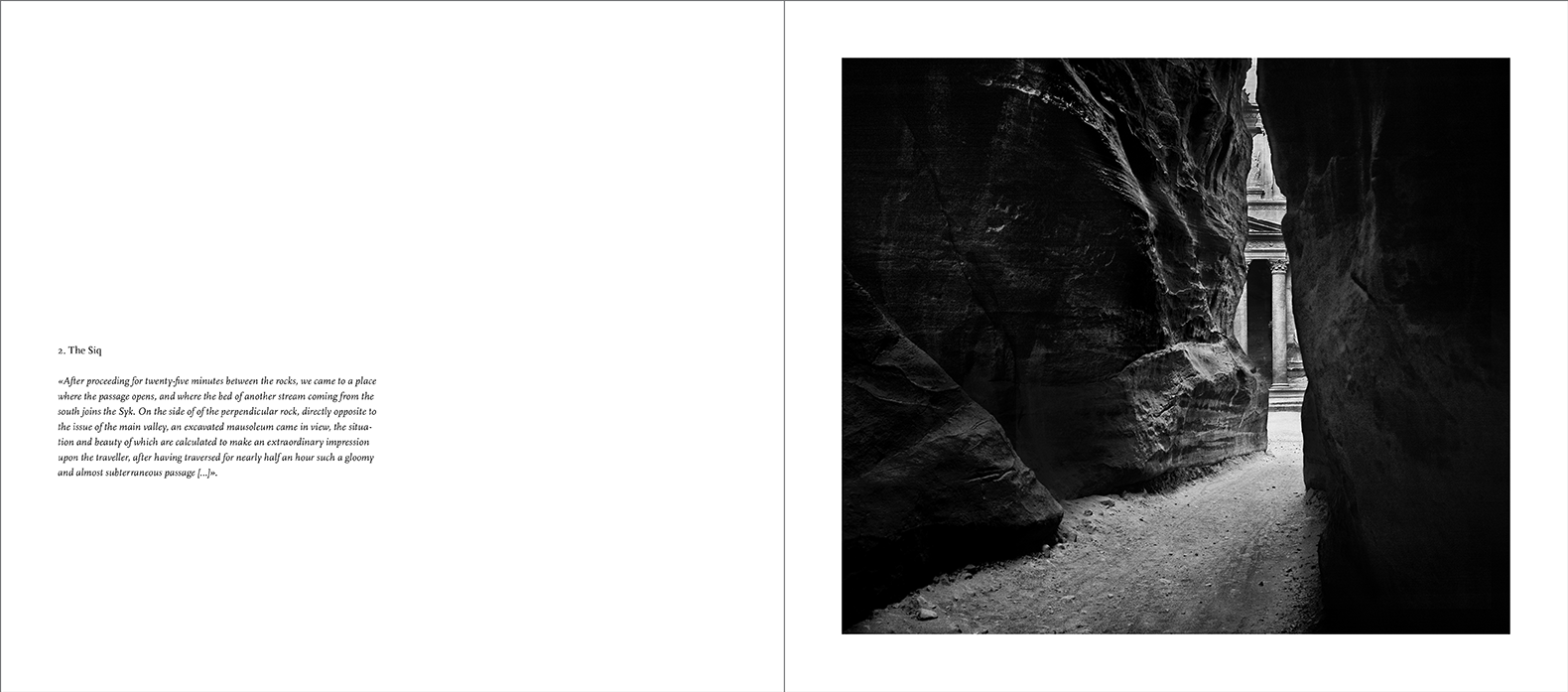

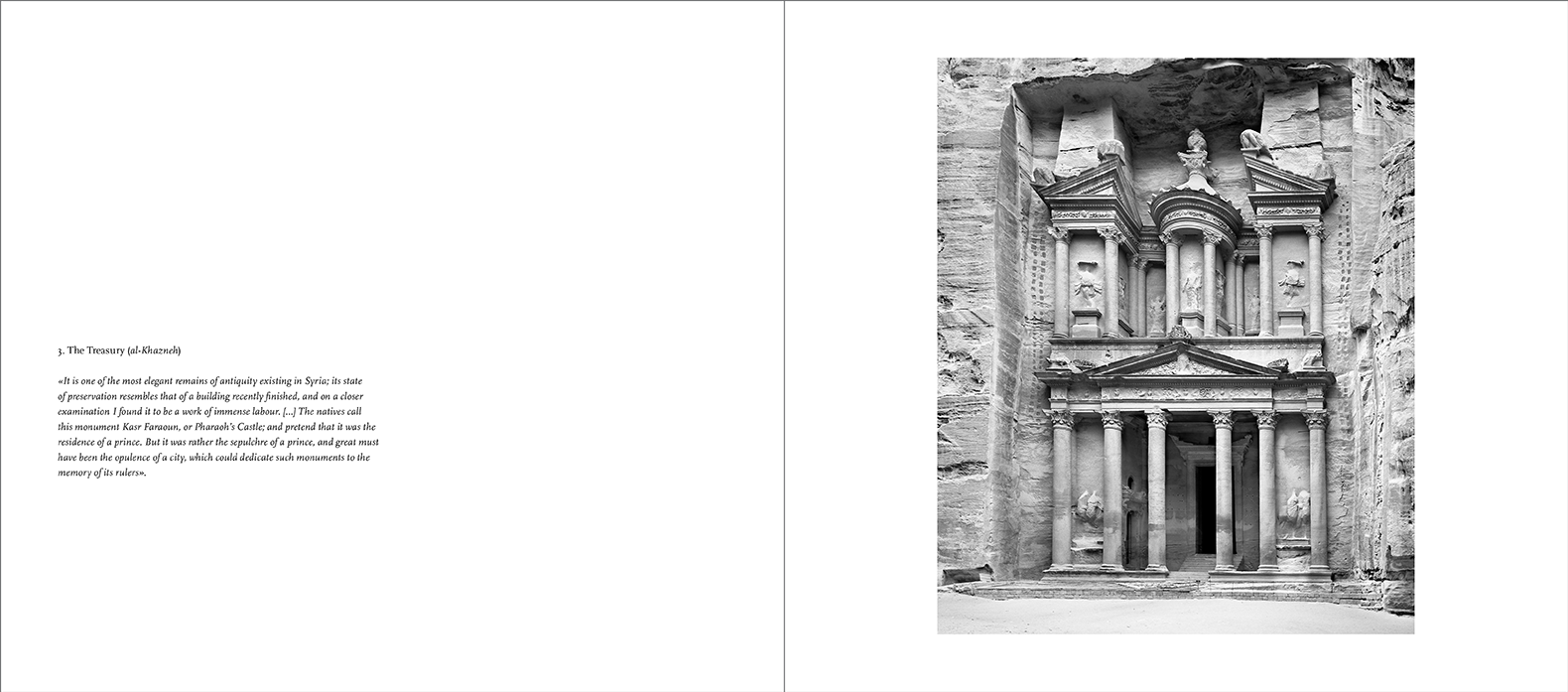

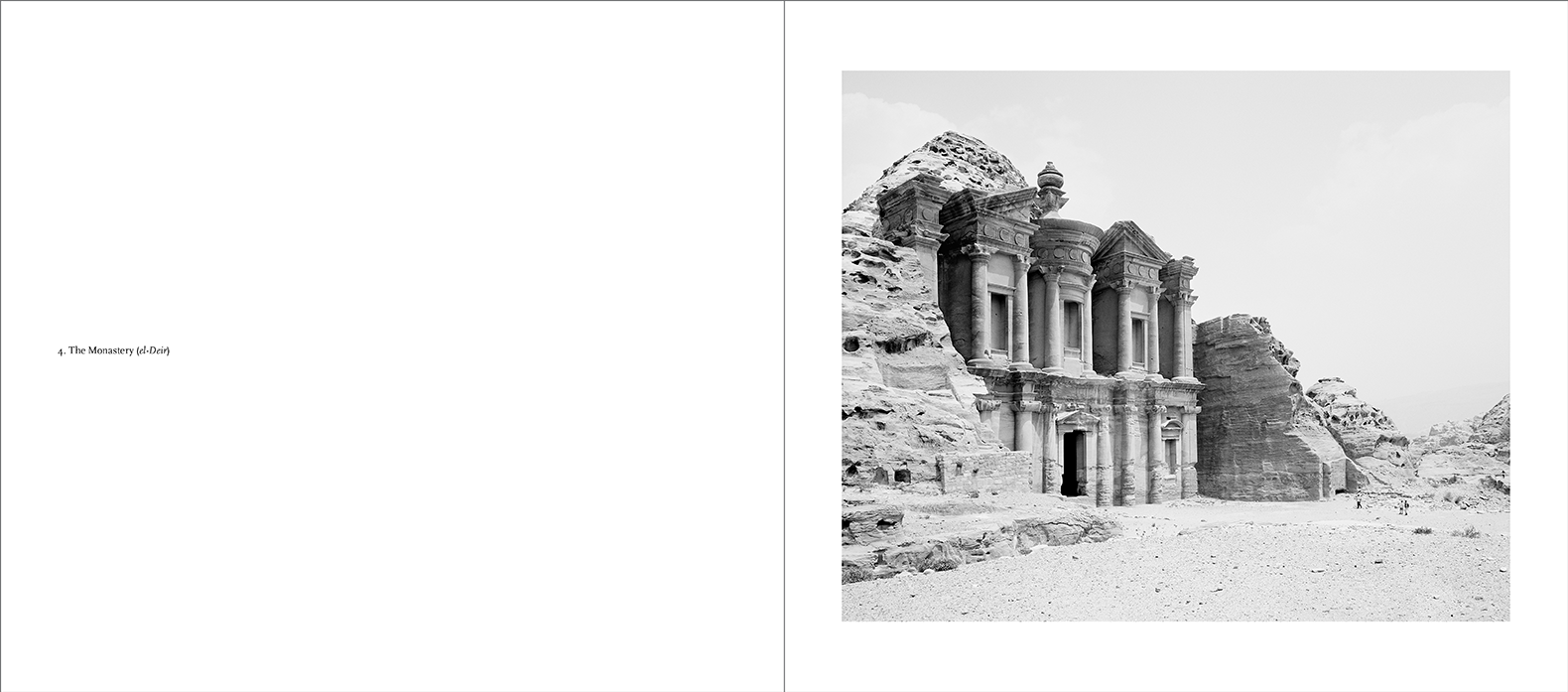

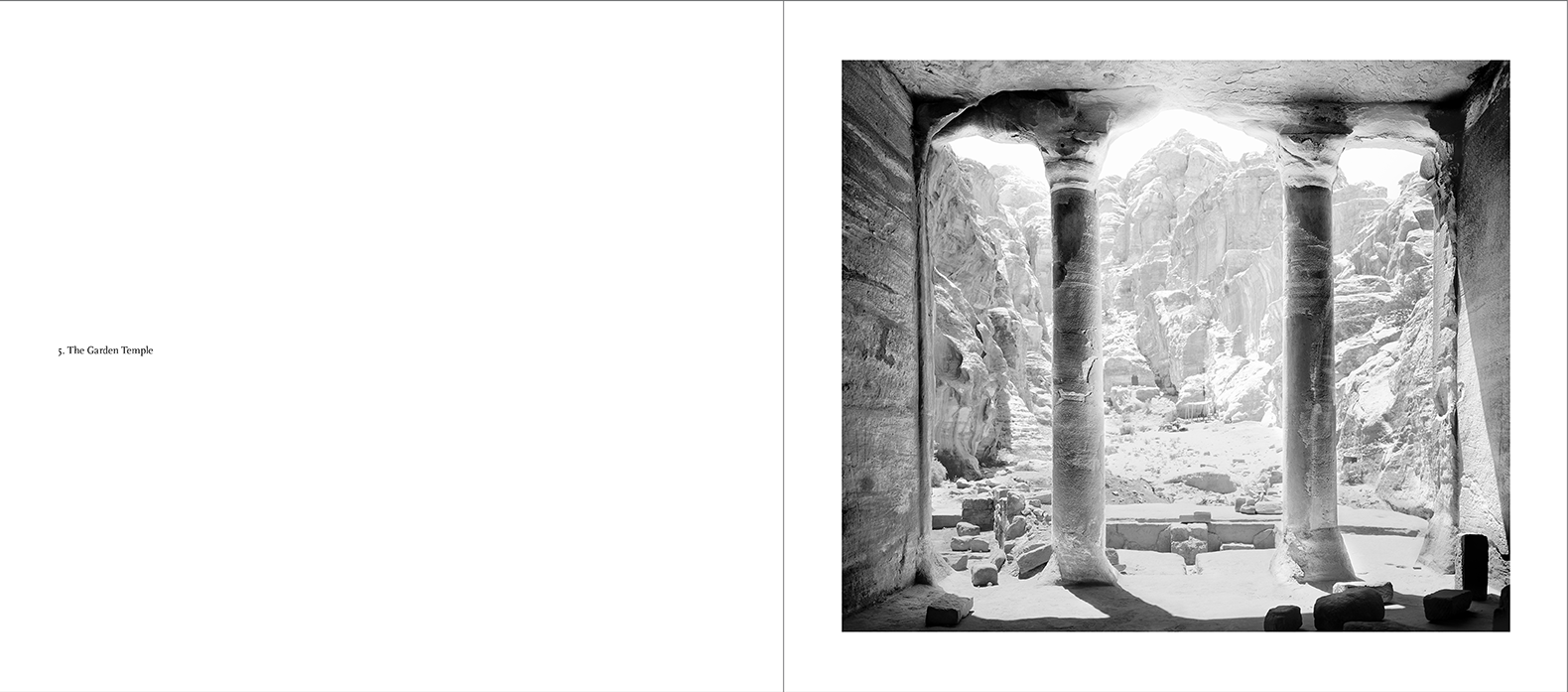

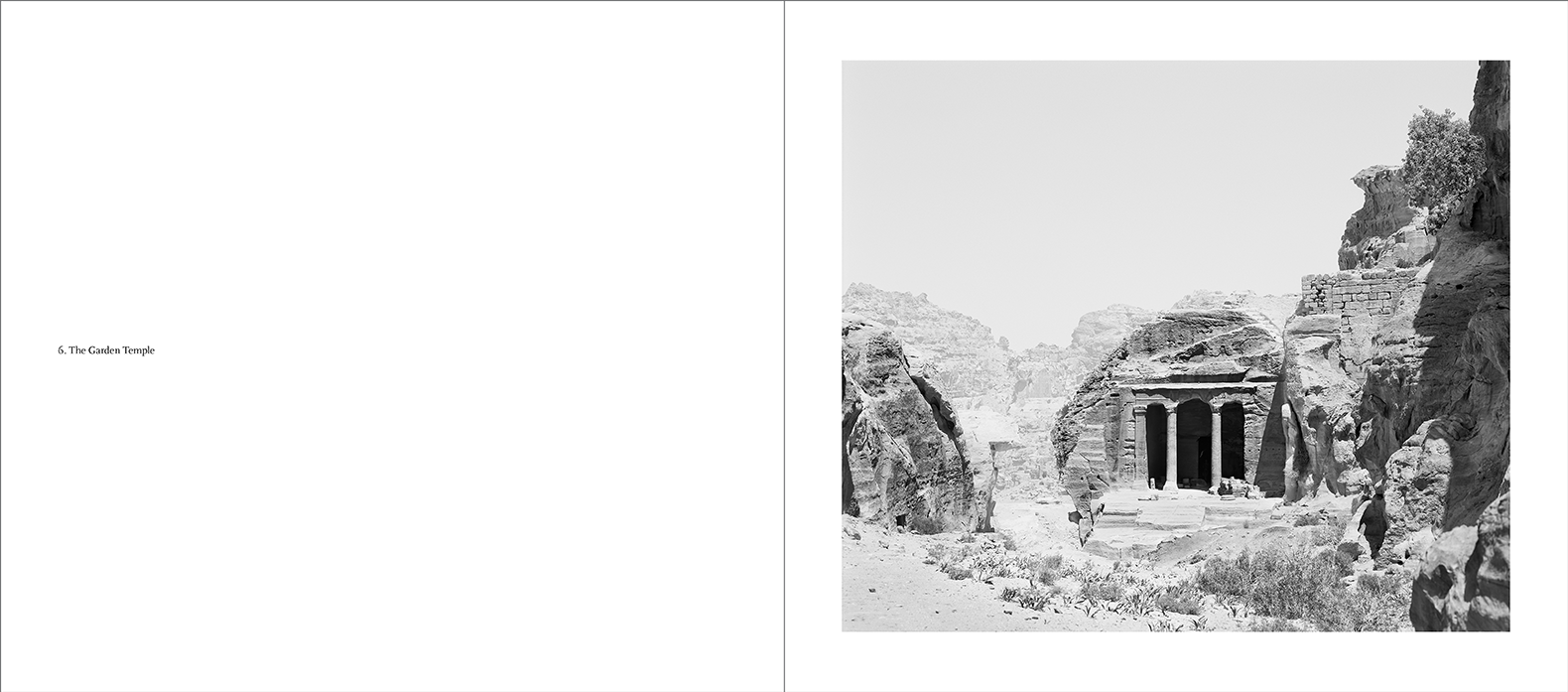

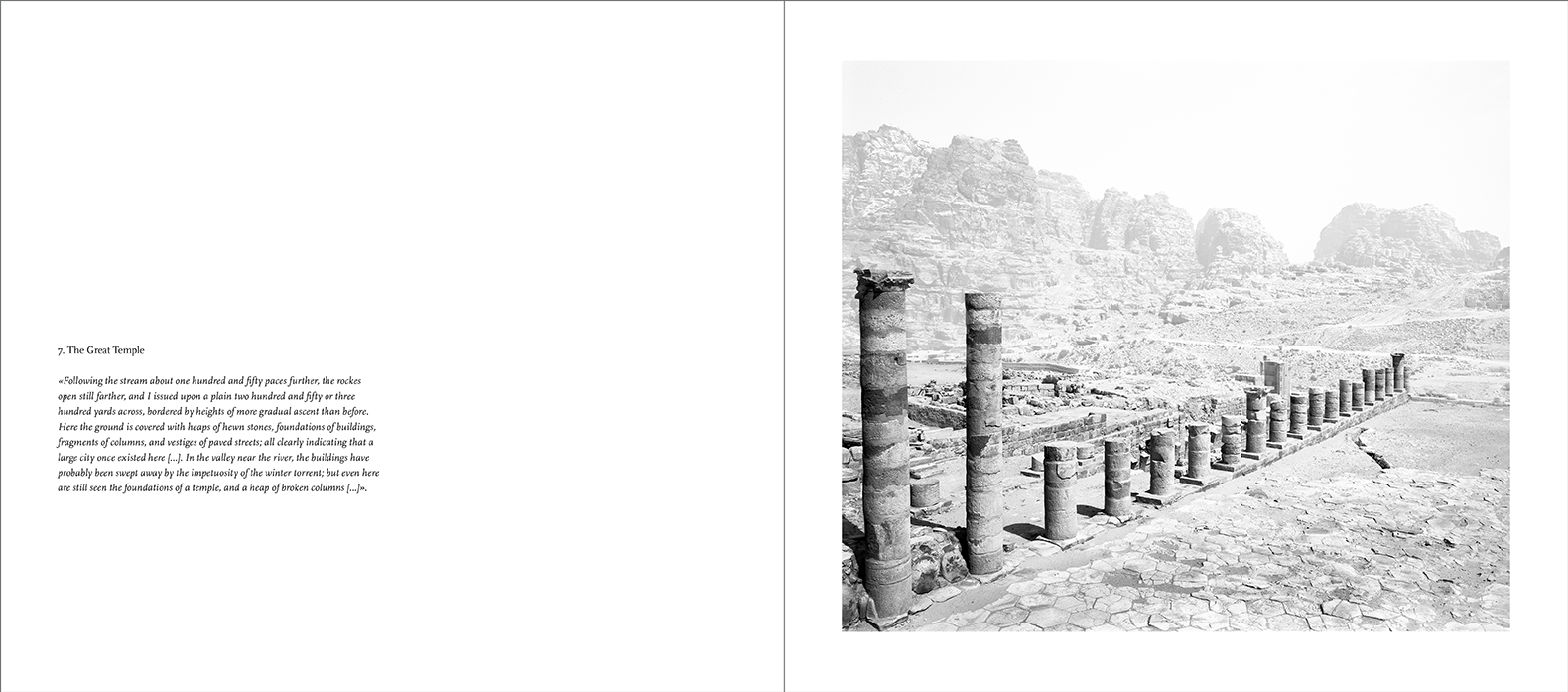

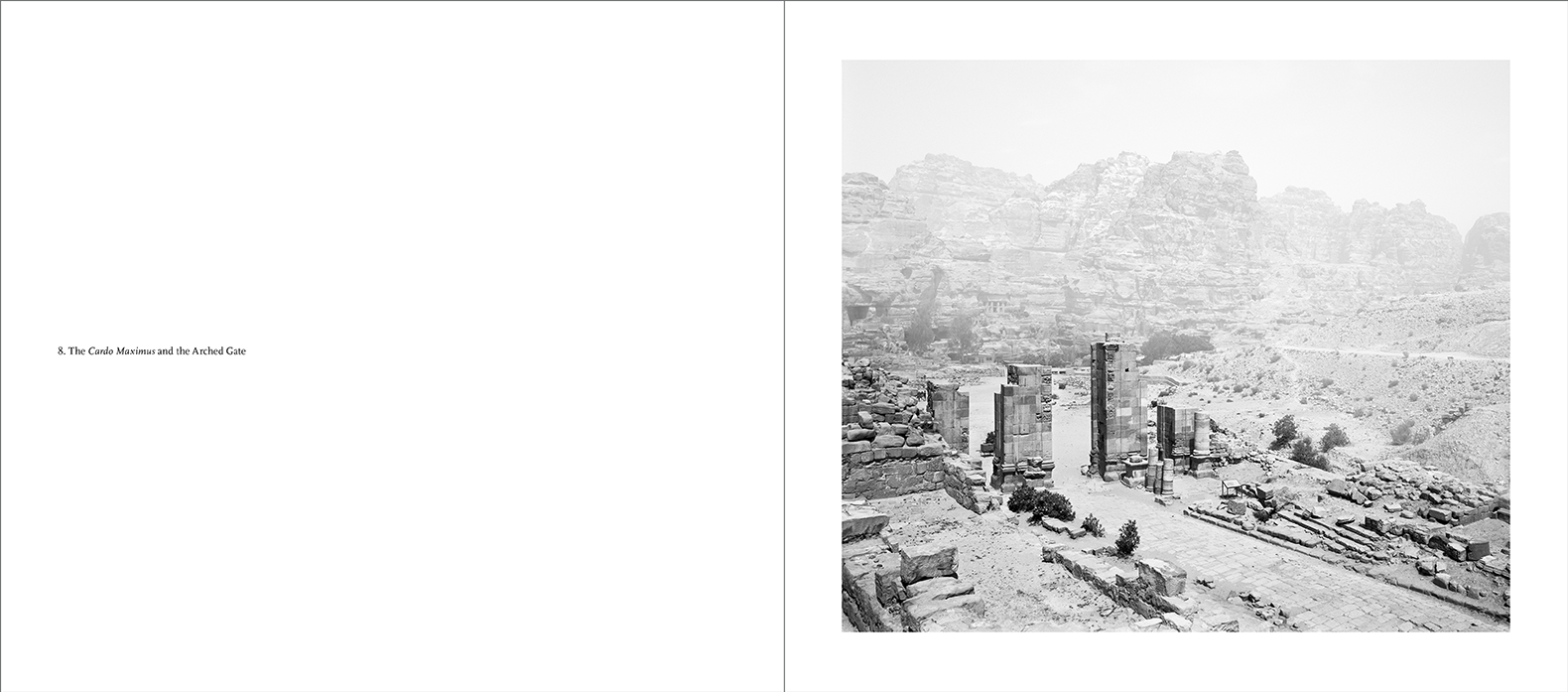

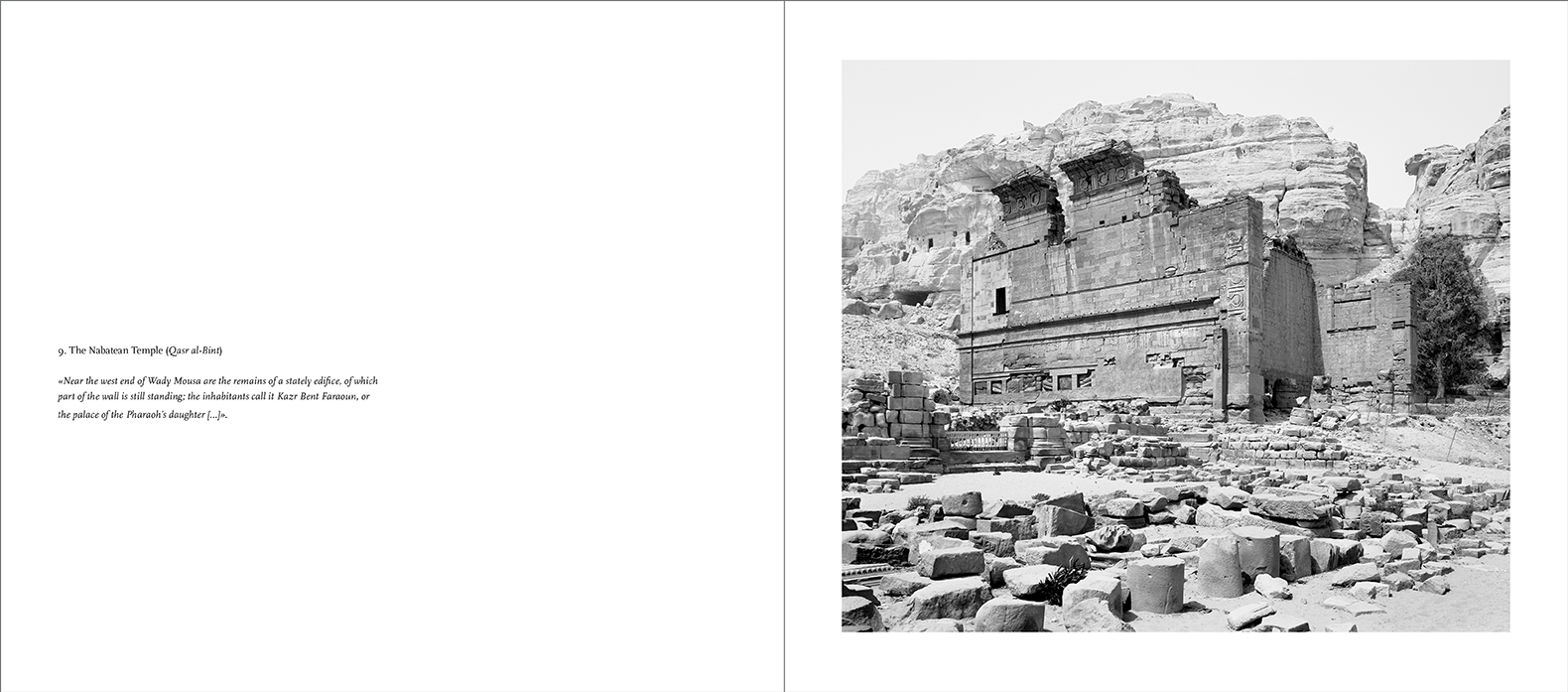

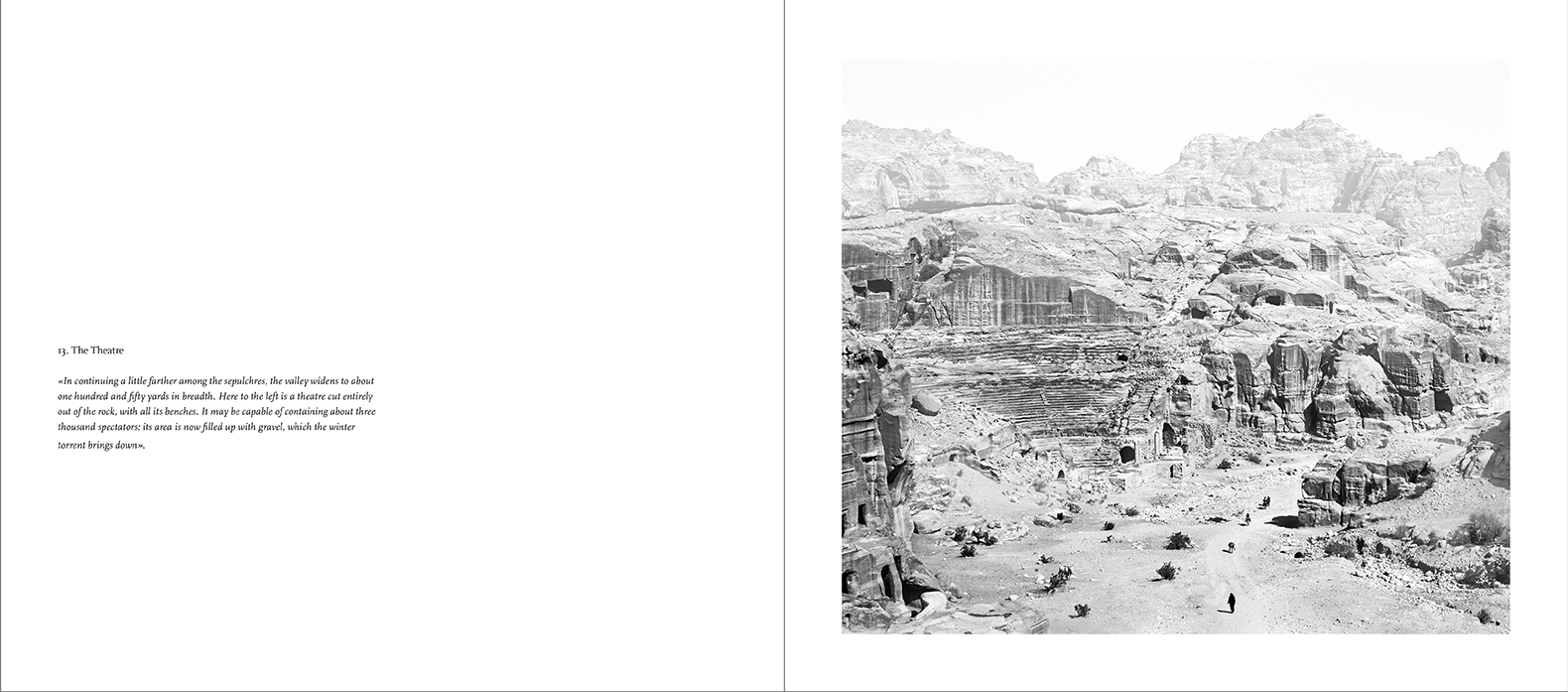

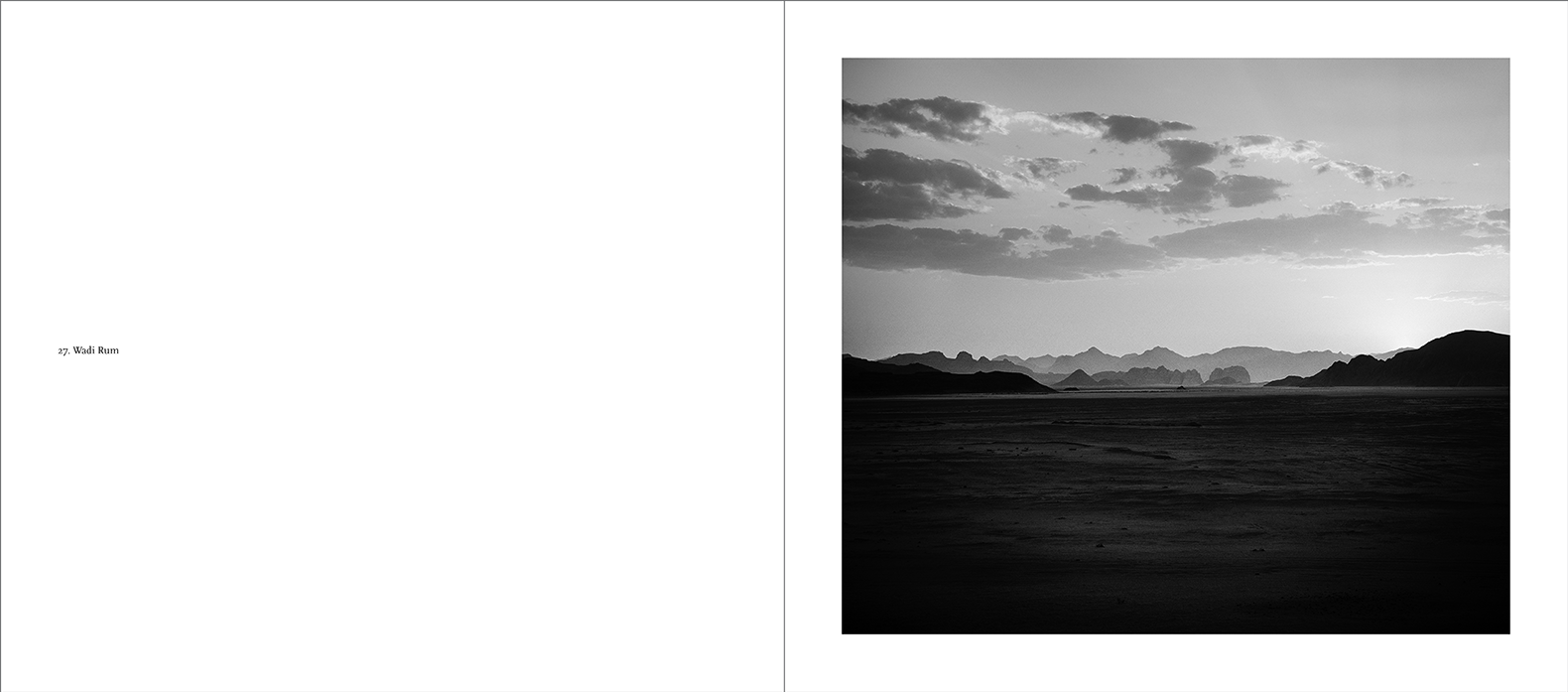

Read lessA JOURNEY TO PETRA AND WADI RUM

27 x 24 cm, 68 pages, 35 tritone plates with varnish, hardback, English edition. Momentarily out of stock.

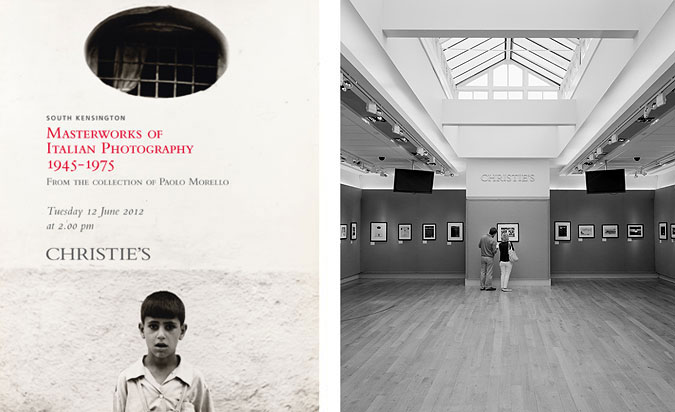

Masterworks of Italian Photography from the Collection of Paolo Morello

London, Christie’s South Kensington

12th June, 2012

Italian Realism. Masterpieces from the Collection of Paolo Morello

Moscow, Big Manezh

March, 18th - April, 24th 2011

La fotografia in Italia. Capolavori della fotografia italiana dalla collezione Paolo Morello

Milano, Fondazione Forma

February, 12th - June, 2th 2010

Petrodvorec, Marly Pavillion

August 2014